Making an affordable trailer in composite means in reality introducing new technology to a conservative market. There is no doubt that every university in the world with a minimum of composites expertise can design and make a prototype trailer out of composite materials. Making this trailer do the job for a certain period is something else. Manufacturing it on an industrial scale, selling it to the market, and making a profit out of it is another thing altogether. No one has done this except for Composittrailer in Belgium.

This step towards industrialisation is bringing about a radical change in the total culture of the company. It changes the thinking of the engineers, the way of working in the shop, the handling of materials and last, but not least, the approach to customers and the market. This is radical innovation. Making a trailer work is a small part of the effort involved in bringing that trailer through an industrialisation process to the market in a profitable way.

Radical innovation

There is a huge difference between radical innovation and incremental innovation. Changing a car door or hood from sheet metal to a composite part of sheet moulding compound (SMC) is an incremental step. This change in materials is not drastically changing the behaviour of the car, nor does it involve a drastic revolution in the production processes of the car plant. Changing the chassis of the same car to a composite structure is radical because it means a complete change in engineering, assembly process, marketing and after-sales services. It will definitely turn the company upside down. For this reason, no major trailer builder will make this radical step.

A trailer in composite material will be a radical innovation project.

Academic research has proven that changing large numbers of steel parts to composite parts is ultimately not cost effective and it is only affordable if other advantages also result. Corrosion and weight reduction are typical examples. In most cases, these additional advantages cannot be charged to the customer since there is no willingness to pay for them. Unless a radical move makes a complete structure affordable to the customer, and brings enough advantages, the new product will not have a chance. In the trailer business, this means going all the way in changing the complete chassis structure to composite material.

Composittrailer carried out trials to change the steel concept gradually towards composite materials. It cannot be done. Mixing metal and composite in a structure with high dynamic loads and subjected to various temperatures is always penalised by broken metal parts. Back in 1994 six such hybrid trailers were made. Each one has now travelled over 1 million km and every year the metal parts are welded. This is the second reason why going for trailer in composite material means changing the whole structure and not just some parts here and there.

Why composites?

A truck trailer is composed of a metal structure and parts. Today, the real product innovation is done by axle, brake and suspension suppliers on the products they make. In Europe, for example, the axle and suspension market is dominated by four companies, and only three brake systems are available. So the only part of the trailer that is left to the trailer manufacturer to play with is the structure, and this represents 20-40% of the cost of the trailer. The competitive advantage of a trailer company relies only in a small way on being innovative with the product. The winners are those which are the best in purchasing and organisation of the logistics chain.

Nevertheless, the search for weight reduction is becoming important. Penalties for overloading are becoming more and more important all over the world, so there is a driver for a lightweight trailer.

The trailer structure is one of the few things not defined by rules. European CE obligation stops at the chassis beam and no national regulation specifies the construction of a chassis – that is the responsibility of the trailer builder. As long as outside dimensions, brake behaviour, tyre specifications and lighting meet national and European rules, the chassis structure is the entire responsibility of the trailer builder. This is a dream for innovators. You will have to look hard to find a similar application for advanced composites! Just think of the rules governing the housing market, not to mention the aerospace sector.

The increasing demand for lightweight trailers and the absence of legal technical obstructions makes this development interesting for the small trailer builder. Knowing that the trailer market represents 300 000 units in North America, 100 000 units in Europe and another 250 000 units in the Far East, it pays off to look into this development. This could effectively mean a huge step in total global composites production, and small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) can lead the way.

Trailer design

Trailers are practically as old as human civilisation. Traces of a trailer nearly 8000-years-old have been found in Turkey. Up to the late 1800s, all trailers were made of wood. Only at the end of the 17th century springs were put on and bearings on the wheels were only available at the end of the French Revolution.

The use of wood as a structural part has been developed over eight millennia. The Conestoga wagon in Pennsylvania and the Kakebeenwa in South Africa in the 19th century are really pearls of wood craftsmanship. The wagon makers knew what wood to place in which direction in order to have the best shock absorbence and roadworthiness possible. The wagon maker was engineering fibre structures. I guess this made him a builder of trailers in composite materials. It is truly a pity that all this knowledge was lost around the time of World War I with the introduction of steel profiles.

It was only after the ‘60s that engineers started to become interested in lightweight structures again. One of the first to use composite materials in trailer building was Fruehauf in the USA with the FVE2000 in 1982. This concept used pultruded profiles and composite sandwich panels. This idea was quickly taken over by builders in France. Their self-supporting monocoque structures are still successfully used in Europe. These trailers, however, still use steel subframes and axle connections.

Over the last two decades, some attempts were made in the US and Europe to build a trailer chassis in composite material. Only a few made it to a successful prototype stage and these projects stopped before the industrialisation process. The approach of Composittrailer was different from the other projects from the very beginning. The initial basic engineering principles – that all parts must be engineered in such a way that mass production is possible in an affordable way – were never forgotten. An affordable trailer in composite can only be produced in a continuous process. This is also the best way of guaranteeing a consistent, high quality.

A lot of prototypes are in some way technical masterpieces. However, with the existing and available technology, there is no way these trailers can be made in a cost effective way.

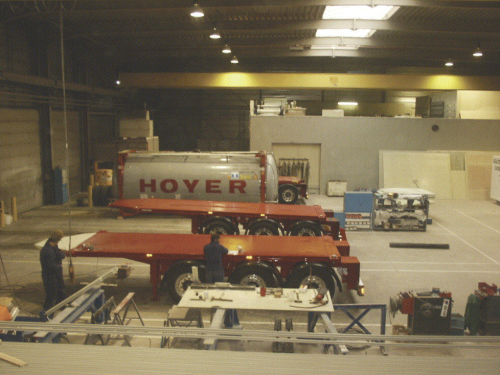

In 2000, Composittrailer started to commercialise a live floor trailer with an empty weight of 6 tonnes. This trailer quickly found its place on the lightweight trailer market. With full aluminium constructions of 9 tonnes, the difference of 3 tonnes was spectacular. But what happened next was surprising. Instead of the competition tuning to composite, the aluminium federation started pushing for more effective structural aluminium engineering. This resulted in bringing the average weight back to 7.8 tonnes, cutting the gap in weight in two! This, combined with teething problems in the first years of the new composite product, was not easy to overcome. However, the early success of Composittrailer and the millions of kilometres proof of the product made several trailer builders interested and Composittrailer started working together with two of them. A partnership with Renders for the container chassis and Benalu for the live floor trailer meant a second start for Composittrailer. With one to two container chassis a day and one live floor trailer a week, Composittrailer now processes 8-10 tonnes of composite material a week.

Since 2001, Martin Marietta Composites in the USA has been using Composittrailer's patents and know-how to build and market trailers built entirely in composite material for the American market. With 280 000 trailers sold each year, North America is considered the largest market in the world for this type of towed vehicle. Martin Marietta Composites believes that potentially more than 50% of this market could be captured by trailers made out of composites. Martin Marietta Composites adapted the initial European trailer design to a specific North American type trailer.

Unique technology

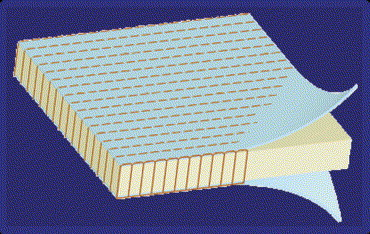

Over the last ten years Composittrailer has built up a unique technology. The need for extremely strong panels for the side walls of the trailers pushed Composittrailer's engineers to develop a unique product: the Acrosoma® panel. This technology can viewed as separate from the trailer technology, although it is essential part for it. In this tri-dimensional reinforced sandwich structure a reinforcement fibre is ‘stitched' through the sandwich panel in the z-direction. As a result the top and bottom skins are ‘tied’ together, which leads to a rugged sandwich panel that has better performance in delamination resistance than a conventional sandwich panel.

The Acrosoma production machine combines tufting (a textiles process) and pultrusion (a composites process), two reliable and proven techniques, to produce a strong panel at 150 m2 per hour. A foam core is pulled through the entire machine. First, this foam core is covered on top and bottom by a mat of glass fibre and stitched with aramid fibre with a tufting machine. A wetter injects vinyl ester and the combination is heated up in a die. The cured panel is pulled through the whole process by a puller, each time the needles from the tufting machine have left the core.

The design of the machine allows the production of different shapes of panel with thicknesses up to 80 mm. Each thickness requires a separate in-feed, wetter and die. Numerous of skin materials, foam types, resins and stitching fibres can be combined. In this way the panel can be tailored to specific needs.

Future

Composittrailer made a first step by changing the chassis structure to a composite one. No doubt that more weight can be won by detailed engineering. According to the 80/20 rule, this would mean that big efforts will have to be made for a small gain. Composittrailer brought the container chassis weight down from 3500 kg to 2800 kg. Knowing that the axles, tyres and suspension weigh around 2 tonnes, this means that the structure has been brought down from 1500 kg to 800 kg, practically cut in half. The next logical step will be to look at the suspension and axles. Two tonnes is a lot of weight and if this could be brought down to half, another tonne of weight will be found. But that is the next story.