Researchers in the College of Science at Virginia Tech have developed a material that is up to 40 times faster at desalinating small batches of water than other materials available today.

Guoliang ‘Greg’ Liu, an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry, has been researching the design and synthesis of porous carbon fibers for the past few years. This material is composed of long, fibrous strands of carbon with uniform mesopores of approximately 10nm.

Liu sees the primary application of his porous carbon fibers in the automotive industry, where similar, but less efficient, materials are already used as the external shells of some luxury cars. Now, in a paper in Science Advances, Liu reports a new application for this wonder material: capacitive desalination.

"Because of the high surface area of the porous carbon fibers, we can store a lot of ions," said Liu, who is also an affiliated faculty member of the Macromolecules Innovation Institute. "Because of the interconnected porous network, the ion movement is very fast inside the pores."

The best-known method of desalination is reverse osmosis, in which seawater is forced through a semi-permeable membrane to separate salts from water. Liu said the materials and process in reverse osmosis are relatively mature now, and this energy-intensive process is efficient at treating large quantities of water. Capacitive desalination using porous carbon fibers, on the other hand, requires much less energy for treating water with low salinity.

"The advantage of our process is that we can have much faster, much higher capacity, and more energy efficiency at this concentration range," Liu said. "Under our experimental conditions of around 500 milligrams (of salt) per liter, it's going to be way more expensive if you use other means because you're trying to get a little bit of salt out of the water."

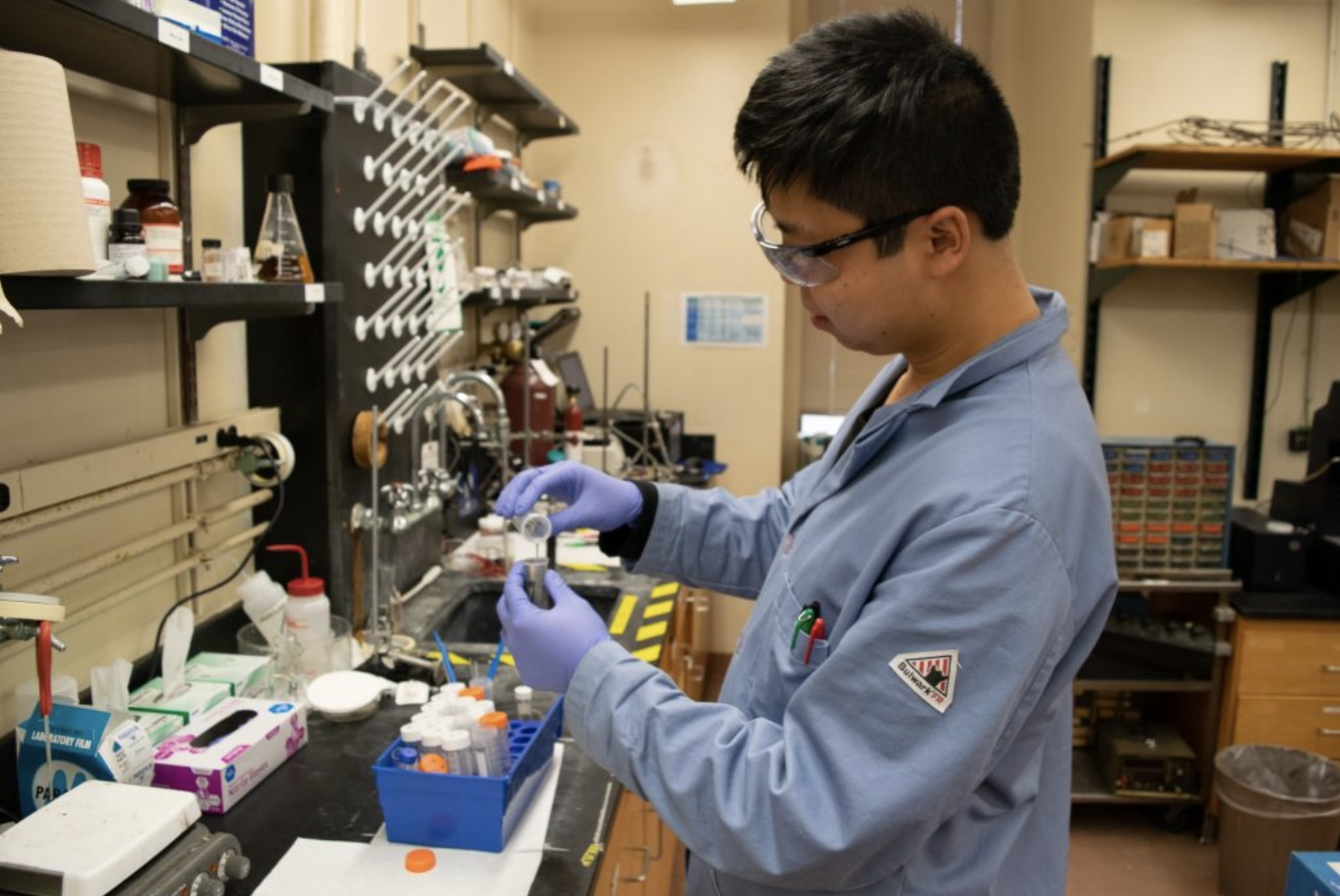

According to Tianyu Liu, a postdoctoral research associate in the Liu Lab and first author of the paper, this new desalination process is simple: he places two pieces of porous carbon fiber into a saline solution, and then applies a voltage through the fibers. This applied voltage creates an electrostatic force that naturally attracts the salt ions out of the water.

"Capacitive desalination treats the water using electrodes with high surface areas and electrical conductivity," Liu explained. "The potential you apply reduces the ion concentration in water, and then you discharge the ions to regenerate the electrodes. These processes are repeatable with negligible loss of desalination capacity."

Liu notes that while this material has shown great results, the research team has only shown a proof of concept for desalination. They are now looking for engineering laboratories on campus and across the country to help scale up this research and design large-scale desalination cells.

Liu's porous carbon fibers are promising for use in applications as diverse as batteries, cars and desalination, and he's looking to see what else it can do. "We hit the jackpot," Liu said. "We want to explore all of the advantages of this material. This material has many great properties, and there are so many things we can do."

This story is adapted from material from Virginia Tech, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.