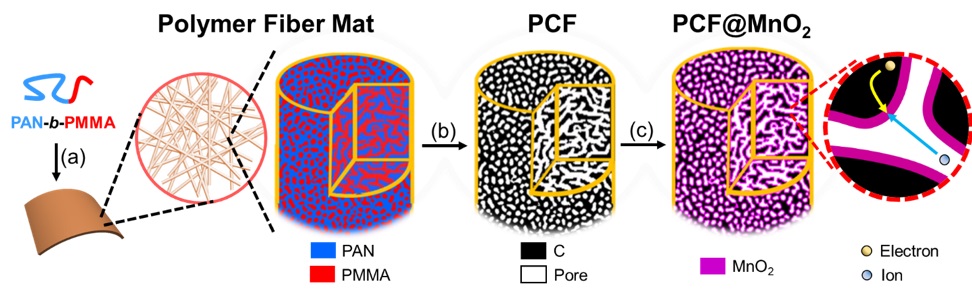

Guoliang ‘Greg’ Liu, an assistant professor of chemistry in the College of Science at Virginia Tech and a member of the Macromolecules Innovation Institute, has been working on developing carbon fibers with uniform porous structures. In a recent paper in Science Advances, Liu detailed how his lab used block copolymers to create carbon fibers with mesopores uniformly scattered throughout, similar to a sponge.

Now, in a paper in Nature Communications, Liu reports how these porous carbon fibers can achieve high energy density and high electron/ion charging rates, which are typically mutually exclusive in electrochemical energy storage devices.

"This is the next step that will be relevant to industry," Liu said. "We want to make an industrial-friendly process. Now industry should seriously look at carbon fiber not only as a structural material but also an energy storage platform for cars, aircraft and others."

Carbon fibers are already widely used in the aerospace and automotive industries because of their high performance in a variety of areas, including mechanical strength and weight. Liu's long-term vision is to build exterior car shells out of porous carbon fibers that could store energy within the pores.

But carbon by itself isn't sufficient. Although a structurally prime material, carbon doesn't possess a high enough energy density to create supercapacitors for highly demanding applications. Because of this, carbon is often coupled with what are known as pseudocapacitive materials, which unlock the ability to store a large amount of energy but suffer from slow charge-discharge rates.

A commonly used pseudocapacitive material is manganese oxide (MnO2), due to its low cost and reasonable performance. To load MnO2 onto carbon fibers or another material, Liu soaks the fibers in a solution of a potassium permanganate (KMnO4) precursor. This precursor reacts with the carbon, etching away a thin layer, and then anchors onto the rest of the carbon, creating a thin coat of MnO2 about 2nm in thickness.

But industry faces a challenge with MnO2. Too little MnO2 means the storage capacity is too low, but too much creates a thick coat that is electrically insulating and slows down the transport of ions. Both contribute to slow charge-discharge rates.

"We want to couple carbon with pseudocapacitive materials because they together have a much higher energy density than pure carbon. Now the question is how to solve the problem of electron and ion conductivity," Liu said.

Liu has discovered that his porous carbon fibers can overcome this impasse. Tests in his lab showed the best of both worlds: high loading of MnO2 and sustained high charging and discharging rates. Liu's lab proved they could load up to 7mg/cm2 of MnO2 onto the porous carbon fibers before their performance dropped; that's double or nearly triple the amount of MnO2 that industry can currently utilize.

"We have achieved 84% of the theoretical limit of this material at a mass loading of 7mg/cm2," Liu said. "If you load 7 mg/cm2 of other materials, you will not reach this.

"In a long-term vision, we could replace gasoline with just electric supercapacitor cars. At this moment, the minimum of what we could do is to utilize this as an energy storage part in cars."

Liu said that a short-term application could be utilizing the carbon fiber parts to deliver lots of energy in a short period to accelerate cars faster. But Liu is also looking beyond the automotive industry into other transportation applications.

"If you want a drone to deliver products for Amazon, you want the drone to carry as much weight as possible, and you want the drone to be as lightweight as possible," Liu said. "Carbon fiber-based drones can do both jobs. The carbon fibers are strong structural materials for carrying the goods, and they are energy storage materials to provide power for transportation."

The research on this material is accelerating in Liu's lab, and he said he still has many more ideas to test. "What I believe is that porous carbon fibers are a platform material. The first two papers, we focused on energy storage for vehicles. But we believe that this material can do more than that. Hopefully we'll be able to tell more stories soon."

This story is adapted from material from Virginia Tech, with editorial changes made by Materials Today. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of Elsevier. Link to original source.