So you want to build a wind farm. Good for you. With the global drive towards a low carbon economy, it is surely the right way to go for many individuals, companies and, indeed, Governments around the world. As information from the Canadian Wind Energy Association (CanWEA) points out, “from large energy companies to individuals looking to supplement their own energy needs, there's a great future in wind energy.”

But while wind energy can make good economic sense for many, planning and developing a wind farm is, CanWEA adds, “a big ask”.

It's not for the faint-hearted, nor for those in any particular hurry. And in many cases it's not necessarily the right option at all.

In fact, when it comes to developing a wind project from A to Z, there is a minefield of potential obstacles, risks to be factored in, and almost certainly some controversy to be faced. Get it right though and, in the words of the Canadian association, the rewards make it all worthwhile.

Key ingredients for success

Successful wind project development needs proper assessment, the right market conditions in place to make it economically feasible, and a great deal of careful preparation and handling. It's the same whether you are talking about one turbine or a thousand, wanting to go onshore or offshore, or are dealing with a private development or a community-owned scheme.

In most countries too, there are a multitude of different approval processes (often at local, regional and central Government level) to go through.

And that's before you even begin to face the practical matters of actually building the thing. Then there's the sticky issue of securing the finance you need (not trivial during a global credit crunch); due diligence issues (technical and non-technical alike); equipment selection; project engineering; construction and grid connection; along with a host of other things to tick off the list. And then when it has been built, the wind farm needs to be run as efficiently as possible to maximise the returns available.

Every country has its own specific characteristics, rules and conditions that come with developing any energy project, and with them come different risks to be aware of. Some of these will of course affect how a project is developed, and whether or not it can be done cost-effectively. Working with people that have good local knowledge is always a sensible approach to take.

But while there are country-specific hurdles and obstacles to overcome, there are also certain universal steps that any (and all) prospective developers or project owners need to take. And similarly, there are certain words of cautionary advice they would be wise to heed, which will be discussed throughout this series.

So to kick off, just as a local working knowledge of how business is done in any specific country is important, the wisest course of action for any prospective wind farm owner is to turn to the multitude of experts in the field, to ensure the whole thing goes smoothly and effectively.

Even the biggest companies in power generation do not necessarily have all the expertise they need in-house. Like everybody else, they sometimes need to turn elsewhere for the expertise they require.

A dedicated wind or renewable energy association is likely to be many people's first port of call when seeking advice, but to make sure you are turning to the right people when it comes down to the nitty gritty, you need to know exactly why you need them, and when.

This series of articles aims to help you know just that, and be aware of the issues you need to address.

Patience will be a virtue

Taking a wind project through from initial conception to full operation and beyond is then an extensive process that can take years. According to Australian firm AGL Energy, there is a 6-phase process involved in any wind project:

Kicking off is the pre-feasibility and feasibility phase (or project conception stage as some refer to it).

This is then followed by the development phase, design and planning, construction, handover and close out, and finally maintenance and performance.

Just the main development phase before construction can even begin is a “timely process and requires extensive research, technical reporting and consultation with relevant planning authorities, organisations and members of the local community”, AGL notes.

The initial steps for any project, involve investigating whether it is even feasible to run with the idea and develop it further. As with anything, just deciding that you want to develop wind power – and it actually making sense to take the idea to a stage where some serious time and money need to be committed – are poles apart.

A preliminary assessment as to whether or not there is scope for a project, and where/what the least-cost, most efficient and profitable opportunity lies, may need to be conducted first:

“Designing a wind farm is often a complex and iterative process,” explains international wind and renewable energy consultancy GL Garrad Hassan. “In the early stages the focus is on identifying the approximate size of the project and spotting any show stopping issues before too much expense is incurred.” As the development process progresses, the company adds, “the focus changes to identifying in detail all the issues which may influence the final size and layout of the project, and to optimise development within those constraints”.

So the twin goal is to minimise risk while maximising the return on investment.

Generally, the pre-feasibility stage involves conducting a low cost analysis of various potential sites. This stage often involves pre-selecting sites, preparing a simplified design for the best sites, choosing potential turbine models, preparing preliminary cost estimates and financial summaries and then drafting a pre-feasibility report.

If the pre-feasibility analysis shows a project to be viable, more detailed assessments then take place to draw up a full feasibility and costing report, after which the main project development stage can begin.

Consultation with local authorities and nearby communities likely to be affected by a project is vital from the outset, and so should be seen as a part of the preliminary feasibility assessment. And it should continue throughout the development process.

“It is extremely important to contact the municipality before undertaking any steps,” suggests CanWEA. “The consultations with municipalities will really help in making a project successful. Take the time to talk to your municipality and the people in the community who may be impacted directly, and also indirectly. Engage them early in the planning process, answer any questions and/or concerns that they might have, and keep an open dialogue with them throughout the whole development.”

British industry association, RenewableUK agrees: “Community support and involvement is essential to planning for wind energy. For a relatively new technology to proceed through the planning system, it is important that the local community understands both the need for wind power and the way in which it coexists with other aspects of their local environment.”

Where to build – testing the wind regime

“Location, location, location.” The mantra of many a real estate agent and broker. And so it should be too for anyone looking to invest in wind power. After all, if there is no wind, then there is no wind power. But for a potential project to succeed, just having some wind is not enough.

It has to be sufficient to generate enough electricity, regularly, to bring the required return you are looking for, so wind resource and potential energy field assessments are essential. And this involves much more than just monitoring wind speeds.

“Wind energy success is all about location, and selecting the right site is critical to cost-effective wind generation,” according to SecondWind, an American company established in 1980 which now provides wind resource assessment equipment and services to wind farm owners, developers, and consultants in over 50 countries (see ‘a higher height data wakeup call’ on page 18).

The key question, when it comes to assessing a site's specific wind power generation potential, says CanWea, is simply this: “Is there a strong and consistent wind?”

But sticking your finger in the air for an hour or so will not give the answer. “Several factors are required for a utility-scale wind project to be sited, but the most important of these is a good wind resource,” agrees SecondWind: “Site selection typically begins with wind prospecting, or the search for a good general location for a wind energy facility. Wind data in this early stage may come from maps and publicly available databases of historical climate data. Wind maps provide a rough estimate of the average annual wind at a proposed site.”

The terrain also needs to be suitable for turbine(s) and any related infrastructure. How easy it is to access the chosen site and transform it into a power generation facility – and at a later point maintain it on a regular basis – will also have overall project cost implications. “Wind turbine towers and blades are huge components, and transportation to site needs to be fully considered,” explains RenewableUK. “You need to ensure there are suitable access roads, or take into account the cost of building them.”

The potential impacts of turbines on nearby communications installations such as RADAR; microwave; wireless & cell networks, as well as possible environmental impacts on wildlife, habitats and local communities all need to be assessed also. All of these issues need to be considered and assessed in the early stages.

Environmental impact assessments (EIAs) have grown in particular importance, according to RenewableUK. An EIA is a detailed assessment of all the local environmental data, taking into account issues such as species types, movements and numbers; distance to the nearest dwelling/road; and impacts on local nature or land conservation areas.

“Professional advice should be sought from a consultant to ensure a comprehensive EIA is undertaken that can stand up to scrutiny,” the organisation warns. In other words if an EIA does not come up to scratch, the project won't get far out of the planning process starting blocks.

Meantime, another vital factor in determining the success of a proposal is proximity to the electricity grid, notes CanWEA and others. “Many questions must be answered at the pre-planning stage: Does the energy carrier have space for the electricity? Will your site need upgrading? How will it connect to the grid and who will pay for that connection? The answers to these questions vary by Province in Canada for example.” And the same is true in other countries of course.

Site selection is obviously then one of the first considerations, and once you have decided on potential locations for your project, the first thing to do, assuming you are not the landowner, is actually try to secure access to the land via negotiations with the landowner, so that you can assess the wind at those sites itself. This may involve negotiating an option on the land – should the project proceed and gain all necessary approvals (firm land lease agreements with the owner are generally negotiated once approval has been granted).

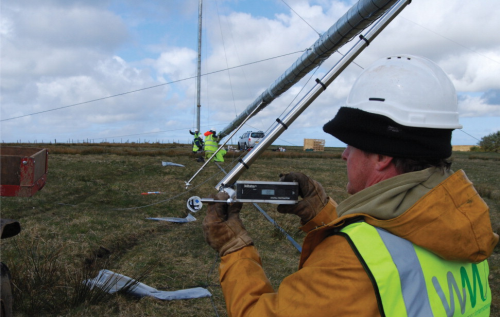

More detailed wind resource assessments, using specialist equipment such as anemometers, met masts and specially-developed software, are typically then used to evaluate the quality of wind on a given site for a period of at least one year (see case study on page 15). Wind speeds, direction, variability, and a host of other factors all need to be monitored and assessed scientifically. And it is at this point that in most countries the first major application for planning approval has to be made, in this instance, for the met mast if there is not one in the area already.

“It is standard practice to utilise meteorological masts to measure meteorological data at a potential wind farm site,” continues GL Garrad Hassan, which has been providing measurement solutions for nearly three decades, from management of mast installation and ongoing maintenance to an online data management service. “The installation and maintenance of meteorological masts is a significant cost during the development process of a wind farm,” it says:

“High quality meteorological data from a site is a key requirement for optimising the design of the wind farm, predicting the future energy production, and also as an input to selecting appropriate turbine technology for the site.”

However, the wind speeds required for cost-effective wind generation will vary depending on several factors, adds SecondWind. These include the eventual land, equipment, and infrastructure costs, the price that is paid for the electricity generated from the wind farm, and the actual cost of money secured via loans and credit finance arrangements to construct the project. “When considering wind generation, one important thing to consider is that the power in the wind increases dramatically as the wind speed increases (power is proportional to the cube of the wind speed). Thus, a 10 percent increase in the wind speed, from, say 7 to 7.7 meters per second, translates to 33 percent in energy potential,” says the company.

Of course, conducting such resource and energy yield site assessments is meaningless unless there will be a buyer for the power generated from a project. Indeed, in some countries developers must have power purchase agreements (PPAs) in place before planning permission can be granted. This is so in many provinces throughout Canada, for example, although not all. In some, there is no need for a PPA prior to submitting a planning application. Instead, electricity is bought and sold based on the daily market price.

Next comes the process of trying to obtain all the necessary consents from the local regulatory authorities, before you can actually contemplate the realities of actually building the project (dealing with the planning process will be discussed in the next part of this series).

Along with securing all the necessary planning consents, these initial stages are arguably the most critical in a project's lifespan. Alone they can take years, and require not just a great deal of patience, but skilled implementation to avoid losing the time and money invested.

Even then, the final outcome of the planning process is never guaranteed. And it's the same whether you're looking to build a project in an established market like Europe or the US, or in a young, up-and-coming market like Mexico, Bulgaria or South Korea.

However, there are ways to significantly minimise the risks of a project failing to get the green light for construction. Using the vast array of industry experts and consultants out there will help you to that end.

Gail Rajgor is a writer working across the energy & environment sector. She is the former publisher of Sustainable Energy Developments magazine, and former assistant editor of Windpower Monthly.