Green factor sells

Other material suppliers have noted the stream to green among boat builders. AOC of Collierville, Tennessee, USA, has developed polyester and vinyl ester resin formulations with low styrene content and hazardous air pollutant (HAP) emissions, and low profile performance. Its product line includes Altek polyester and Hydropel vinyl ester resins for hand/spray lay-up, RTM, LRTM, and resin infusion processes, as well as Hydropel and Vibrin polyester gel-coats.

AOC also has a specialised line of EcoTek green resins, with S404-60G polyethylene terephthalate polyester and H164-ACAG-40 styrene free, thixotropic pre-premoted polyester especially suited for marine applications.

| For very large parts, the infusion processes are about the only option, whereas moulders have more choices for small to medium sized parts. |

| Mike Dettre, Business Manager for Closed Mold, AOC |

Mike Dettre, Business Manager for Closed Mold, points out that AOC offers resins suitable for both hand/spray lay-up and closed mould processes.

“We continue to see interest in closed mould processes on behalf of our boat builder customers,” he reports. “In addition to the inherently lower process emissions, the RTM and infusion processes offer significant improvements in material efficiency and part-to-part consistency and uniformity. For very large parts, the infusion processes are about the only option, whereas moulders have more choices for small to medium sized parts.”

Making the point that Class A surface aesthetics have long been an important goal for most boat builders, Dettre notes that “conventional low profile resin technology has been limited in its use due to high exotherm temperatures, and the detrimental impact this high temperature has on typical composite tooling. AOC recently introduced a new low profile marine resin, R-049-CPF-17, capable of delivering Class A surface finish with up to 40°F lower exotherm in high mass areas, which ultimately translates to extended tool life.”

Another AOC innovation helps moulders produce smoother tooling in less time than conventional tooling resins: MoldTru™ LPT-68000 tooling resin can reduce the cost and time by up to 70% to make Class A surface composite tools. Due to lower exotherm heat, up to five layers of tooling laminate can be built at one time without causing surface distortion. Conventional tooling methods require five separate layers, each involving an overnight cure cycle. The net result is shorter lead-time and lower-cost prototype and production tools.

Boat OEMs who have utilised AOC resins include Cabo and Hatteras Yachts, Nordic Tugs, Sundance skiffs, SeaRay sport boats, Chaparral Boats, and for its houseboats, Catamaran Cruisers.

“The majority of warranty claims for marine composites typically relate to gel-coat cracking,” states Dan Oakley, AOC’s Gel Coat Product Leader, who touts Vibrin G515 gel-coat as the supplier’s answer.

“This formulation increases toughness without sacrificing other critical properties, especially heat deflection temperature, which can drop when toughness is improved. Vibrin G515 also demonstrates 8% elongation, which is almost double that of any other comparable gel-coat.”

AOC is in the final testing stages of a new gel-coat technology that is designed to rival paint in both gloss and colour retention.

“According to research results, this product could have double the performance life of other premium gel-coats,” Oakley states.

Flax fibre and OOA come onboard

One doesn’t normally think of prepreg as having eco-potential, but Amber Composites, Langley Mill, UK, is proving otherwise with natural flax reinforced epoxy in its Multiprepg 8020 prepreg line. The flax fabric is Biotex from Composites Evolution, Chesterfield, UK, and is available initially in a 400 g/m2 2 x 2 twill and a 500 g/m2 plain weave.

“Boat builders are interested in this prepreg for its weight savings and better handleability compared to glass, as well as its damping characteristics,” Andrew Spendiff, Amber’s Marine Market Segment Manager, reports. “We didn’t know what to expect with the flax fabric initially, but were pleased to find that we could easily achieve good levels of impregnation with favorable tack and handling characteristics.”

Samples of the flax/epoxy prepreg are being tested by a number of yacht builders.

Out of autoclave (OOA) cure prepregs are also finding favour with boat builders, such as Poole, UK-based Sunseeker, which has successfully used Amber Composite’s E520 carbon fibre/epoxy prepreg in the superstructure on its Model 28 motor yacht. Spendiff states that this OOA formulation offers “processing and cosmetic attractions, as well as significant weight savings. In just one component, the weight dropped from slightly over a ton to around 250 kg. With fuel costs increasing, weight reduction is becoming more important.”

From a features design perspective, this weight savings allowed Sunseeker to add a huge, wrap-around window on the 28 that greatly enhances boater experience.

Additional development initiatives under way at Amber Composites focus on E525, its next generation OOA prepreg with enhanced surface finish and handleability, now in final stages of customer testing and close to commercial launch; OOA prepreg for tooling of large structures, featuring longer outlife; and a research effort into combining polyester gel-coat systems with epoxy prepreg materials, thereby enabling customers to use preferred gel-coats with the benefits of a prepreg backing.

Spendiff suggests potential benefits as reduced wall thickness and consistent part thickness, weight reduction, a cleaner process, and reduced layup time. The supplier also offers additional tooling systems from WB0700 epoxy boards for direct tooling and close contour casting and paste for plugs and direct tooling.

Campion’s Squish Chalet

One could toss a captain’s hat anywhere across the deck of a Campion boat and land on components built with ‘green’ composites. Since 2008, the company has specified only Envirez bio-based polyester and Maxguard low emission gel-coat, both from Ashland Performance Materials, Dublin, Ohio, USA, and EcoMate polyurethane flotation foam from Foam Supplies Inc, Earth City, Missouri, USA, in its new boat construction. Campion Marine operates out of Kelowna, BC, selling 55 models over their five brands – Chase, Allante, Explorer, Svfara, and Infinyte, ranging from 9 ft to 30 ft in 30 countries.

These efforts, along with some coring used in stringers and floors made from recycled plastic bottles and lean manufacturing efforts to reduce the company’s overall operating energy, garnered Campion the first Eco Award from Boat Magazine in 2010 and the Safeguarding the Environment Award last year from the Canadian Safe Boating Council.

Some 90% of Campion’s manufacturing is conducted using open moulding processes and has been since the family business was founded in 1974. Ashland’s Envirez corn/soy/polyester bio-resin dominates in these operations. The resin delivers parts to with surface elongation improved by up to 2.5 times, and the bio-resin also delivers a hidden benefit.

“The elasticity of the Envirez helps release parts from the mould, which can reduce part stress, says Brock Elliott, Campion’s president. “Also, our Barcol hardness values are up 15%. We believe Envirez gives us a better cure and stronger parts.”

The other 10% of this OEM’s manufacturing involved vacuum infusion until recently. Elliott explains that the company now uses a liquid moulding process they call ‘squish,’ because parts are made when moulding putty is squished out of the laminate by nominal clamping force (60 psi).

“We call our production area for moulding these components the ‘Squish Chalet,’ a takeoff on the popular Canadian restaurant, Swiss Chalet,” he explains.

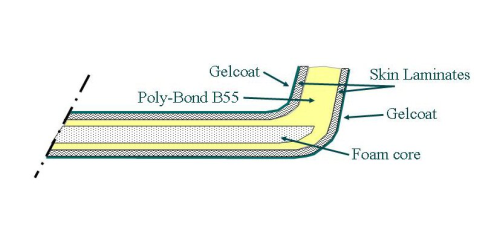

The process and white, low-density polyester-based moulding compound, Poly-Bond B55-LV, were developed by ATC Formulated Polymers, Ontario, Canada. ATC calls this process low pressure compression moulding, one that’s been around for some time in different formats.

“Our version works particularly well with several polyester moulding compounds we formulate, particularly Poly-Bond B55-LV that is well suited for appearance-critical sandwich constructed parts such as marine hatch covers, panels, and hardtops,” states Jean-Pascal Schroeder, CEO of ATC. “Since 2008, we have refined this closed mould process to gain better control over making a quality part with every moulding cycle.”

Under contract to ATC, Lassi Ojanen, who has over 20 years’ experience in composites in the transportation industry, engineered new tooling and processing parameters, and built the first ‘squish moulding’ development tool with an air actuated clamping system. ATC began demonstration of Poly-Bond B55-LV with this tooling amongst its marine customers in early 2009, and a number of boat builders now use the system in production.

According to Lassi: “Tooling cost for ‘squish moulding’ is comparable to tools made of FRP via traditional hand lay-up, and made with the same materials. What ATC has added is a steel stiffener cradle and counter pressure latches to handle tool closing loads and help keep the tool in dimension. The pneumatic clamping system can be used over several tools, which mitigates cost.”

| Compared to RTM or infusion, this low pressure compression moulding process requires less experience from technicians, offers low tooling cost, and allows the use of highly-filled compound that yields distortion free, two-sided parts with surface quality close to Class A. |

| Jean-Pascal Schroeder, CEO, ATC |

Schroeder adds: “The tooling and process was designed to be highly scalable. One can start with a simple mechanical closing system or one sided tool, which Campion Marine has done, or set up a more elaborate mould closing frame press for higher volume production.”

Regarding B55-LV, Schroeder points out that “our moulding compounds are not well suited or cost competitive for highly structural composite parts. However, some neat resin systems would be very suitable for structural applications using this low pressure compression process. Size of the part would be limited by practical considerations on the tooling. Compared to RTM or infusion, this low pressure compression moulding process requires less experience from technicians, offers low tooling cost, and allows the use of highly-filled compound that yields distortion free, two-sided parts with surface quality close to Class A.”

Campion’s Elliott indicates that “catalysis with B55-LV kicks off in 20 to 45 minutes in our use of this squish moulding process, and total cure is achieved after 60-90 minutes. The mould is unclamped, and the finished part trimmed. Some 75% of the labour and all of the process consumables of other closed mould methods are eliminated.” He adds that “air voids are eliminated, and parts have Class A surfaces on both sides so require no buffing. Our employees aren’t sticking their heads into a fumes bucket as this process has no odour, and we can easily incorporate 3D weave of glass and aramid fiber into the laminate.”

Virtually all of Campion’s small parts – such as hatches, glove boxes, fish lockers, and cooler lids – are made using this process.

The marine market plunge isn’t far from Elliott’s mind: “It’s very tough out there.”

Campion has diversified by producing moulds and parts for other OEMs, and one example is Vector Powerboats’ (also of Kelowna) 40 ft V40 with retractable wings, in both commercial and racing versions.

Elliott calls the path to green up his company’s manufacturing operations a continuing journey, and he’s working now to create a recycling source for his FRP trim and to go to bio-based upholstery foam. He says his buyer profile is changing, as consumer consciousness is affected by the challenged economy but also with more individual awareness of the impact of every product over its life cycle in the global environment.

Pirate-busting nano-float

The prototype for a new generation of specialised military/security application boats that are remarkably lighter, consume far less fuel and cut carbon emissions by two thirds has already completed sea trials and transitioned into production. Design, performance and FRP materials were proven in the Piranha, a 17 m (54 ft) long, unmanned surface vessel (USV) built by the Seattle-based marine division of Zyvex Technologies (headquartered in Columbus, Ohio, USA).

Key to achieving the Piranha’s light, stiff, strong, fuel efficient performance is the enhancement of continuous carbon fibre/epoxy prepreg with carbon nanotubes (CNT) in the company’s Arovex product, typically loaded at 35-40/60-65 resin-to-carbon fibre ratio, with about 1% CNTs. Arovex is available in standard, intermediate and high modulus carbon fibre, or with glass, and as a unidirectional, woven or knitted material.

Composite components used in Piranha were manufactured at 80°C (180°F) and 120°C (250°F) cure temperatures.

Zyvex has had Arovex and its CNT dispersion under development for the past seven years.

“Based on this development time already invested, Arovex is a fairly mature product for us,” states Mike Nemeth, Director of Commercial and Defense Applications. “We have demonstrated the best toughness and strength properties when we use very low loadings of CNTs in our resin systems. This also helps keep the materials cost competitive and simple to process.”

He reports that Arovex had also undergone longer-term evaluation in aerospace application prior to the company’s USV projects.

|

What do canoe and kayak enthusiasts and a farmer in Cotswolds, UK, have in common? Maybe a whole new concept of water/land nature adventuring, with the help of two UK biocomposite material suppliers. Simon and Ann Cooper call their acreage Flaxland and, with flax grown on their farm, have built nine canoe prototypes using flax fabric and linseed oil resin (from flax). The fabric, Biotex 4 x 4 flax hopsack or 3H satin weave, is produced by Composites Evolution, while the EcoComp UV-L resin comes from Sustainable Composites. Net weight of the ultralight yet durable biocomposite canoes: just under 12 kg and, for racing, 8 kg. Simon Cooper explains that typical canoe skins of nylon or polyester fabric are strong in tension but offer no structural benefits in compression, which requires a heavier frame to compensate, “whereas the flax-based fabric skins handle tension and compression equally across the marine plywood and pine frame.” He admits that “finding a fabric that could retain the necessary tear strength in one layer and absorb sufficient resin was definitely a question of trial and error. We found that conventional canvas and linen did not simultaneously provide desired strength and fibre wettability. Biotex fabric is prepared using a twistless technology, and the EcoComp flax resin combined with the unspun flax fibres retain the benefits and strength of woven fibres that appear to us to be lost with conventional resins, resulting in the need for multiple layers in the skin laminate.” Commercial canoe and kayak OEMs currently have Biotex flax fabrics under consideration, such as the Trapper Ecolite made by Tahe Kayaks in Estonia, reports Brendon Weager, Managing Director of Composites Evolution Ltd. “Yacht builders are also looking at it, initially for interior moldings such as headliners, furniture, trim, walls and doors, with eventual roll out to more demanding exterior applications.” He compares Biotex flax fabric to available glass fabric in terms of reduced weight and environmental impact. “The density of flax is around 1.5 g/cm3, or about 40% lighter than glass at 2.56 g/cm3, whilst the energy required to produce flax fibre is reported to be around 9.7 MJ kg,” he reports. “This is 80% less than the figure for glass fibre (55 MJ/kg). Natural fibres can also absorb noise and vibrations, provide an attractive natural aesthetic and are significantly safer and cleaner for workers to handle in production. Also, Biotex fabrics are designed to wet out with resin and drape when woven into fabric exactly the same as glass or carbon fibres.” This year, Weager expects his company to support marine customers with its recently introduced flax reinforcement mat with a flow core, specifically for infusion processes, and flax/epoxy prepreg (with Amber Composites) being trialled by a number of boat builders. EcoComp UV-L resin eliminates the need for expensive cure equipment beyond an ultraviolet light source. Steve Wilkerson, Technical Director with Sustainable Composites/Moveirgo, tells Reinforced Plastics that the resin is 95% plant oil, and has also been tested in the construction of a 2.4 m (8 ft) long, 102 cm (40 inches) wide pram dinghy dubbed the Eco Boat, and a larger rowing punt. He reports that comparative performance testing of laminates made with EcoComp UV-L resin and an industry standard epoxy are underway at Southampton University, “and we are developing an ambient cure version of the resin as well.” So what is Flaxland’s unique concept for getting one’s outdoor fix: combining the extreme portability and durability of the biocomposite canoe with a rugged, light weight bicycle and portage trailer. What greater flexibility to explore both waterways and landscape than by canoeing and cycling? So long as one is able to both row and ride, Cooper believes Flaxland can come up with the partners willing to test biocomposites in both the bike and the trailer. This, he believes, could result in the ultimate independent touring experience characterised by ease of use, safety, and tangible utilisation of renewable, recyclable materials. Current tests involve a 10 kg biocomposite canoe, full-size titanium cycle designed by qoroz of Gloucestershire, UK, and specially designed alloy trailer (total weight of the rig on land, 30 kg). To date, the longest test of this row and ride concept has covered approximately 1000 km by land and 200 km on water. |

“Our staff has developed in-depth understanding of the best practices for cure cycle and drapability with CNT-enhanced Arovex, and we keep the formulation consistent in regards to fibre loading and matrix formulation,” he explains.

Certainly a composite USV designed as an anti-piracy, anti-trafficking security escort for other watercraft represents a most specific niche in the marine market, and the mention of nano-science usually drags the red flag of higher cost with it. Nemeth says Zyvex has interfaced with nearby marine companies, such as Pacific Coast Marine, for consideration of the nano-composite prepreg in their commercial marine designs.

He takes the position that “we’re not competing with most traditional boat builders or material suppliers, and have initially found a market for longer range, more fuel efficient vessels in specialised roles where the benefits of nanocomposites are valued.” He believes that Zyvex Marine Division’s position as a new builder gives them the flexibility to make product line shifts “as dictated by customer interest and demand, now that we have a facility that can design and build with the best materials on the market.”

In its development of new maritime platforms based on the Piranha’s success, Zyvex Marine expects to unveil two additional platforms before year’s end. One of these will involve a partnership with an OEM for finished, lightweight nanocomposite marine components, initially doors and hatches.

“These nanocomposite products will provide up to 66% weight savings when compared with other, heavier products on the marketplace,” Nemeth states.

Buoyant future

Even in today’s stark economy, new-build watercraft utilising different FRP material forms and manufacturing methods crest the horizon of the marine marketplace every day. Reflecting upon the changes in this marketplace, Eric Greene, naval architect, engineer and founder of Eric Greene Associates, Annapolis, Maryland, USA, observes that “closed moulding is essential for creating light weight, ultra high efficiency motor yachts. Though prepregs have been used traditionally on racing boats to improve top end speed, fuel-efficiency and green streaming have now become paramount.”

Greene has focused on multiple projects involving large composite structures for naval, commercial and recreational applications.

“In my view, the outlook for efficient mega-yachts constructed with composite components through closed moulding methods is actually quite bullish.”

“Reduction of weight is key,” agrees Structural Composites’ Lewit. “If we can reduce craft weight, we can reduce engine size, and this sets a positive spiral in motion that ultimately results in lower boat cost and greater fuel efficiency. We need to create the next generation of lightweight fuel efficient craft to reinvigorate the marine industry. Closed moulding methods come into play to reduce component variation so that we can implement more structurally efficient designs.”

“Closed moulding has changed the way we design for manufacturing,” the GRP guru Andre Cocquyt concludes.

“Over the past five years, I have worked on a series of 24 m (80+ ft) long, high speed, carbon fibre vessels. Using vacuum infusion, I find it amazing how well specific properties such as weight and strength can be controlled. Further, by building moulds customised for infusion and using CNC-cut kits, the build can go much more rapidly, with significantly fewer work hours spent in that first phase of construction. By hull number three in this series – a cored hull with complex laminate schedules – the hull lamination was finished within two weeks of prepping the mould, achieving final weight within 250 lbs of the design target. I recall only too clearly those 16-hour wet-preg lay-ups I conducted in the mid-80s, followed by the frantic rush to get the vacuum bag on and remove the excess resin before everything gelled. Even though we were very good at those open mould processes, that was crazy!”

He’s optimistic about closed moulding, but not quite ready to hoist the all-clear flag.

“We’ve made a quantum leap in the past ten years in the marine market, and I think we’ll plateau for a brief period while the entire market embraces closed mould technology, additional automation, CNC and CAD capabilities, and helps this mature and become mainstream. It will take a few more years until we have enough skill capacity in our trade to make this happen, but it will come.” ♦

This article is an excerpt from the feature Whatever floats your boat published in the May/June 2012 issue of Reinforced Plastics magazine.